From Suitcases to Startups: Why Immigrants Innovate

We have a high risk tolerance.

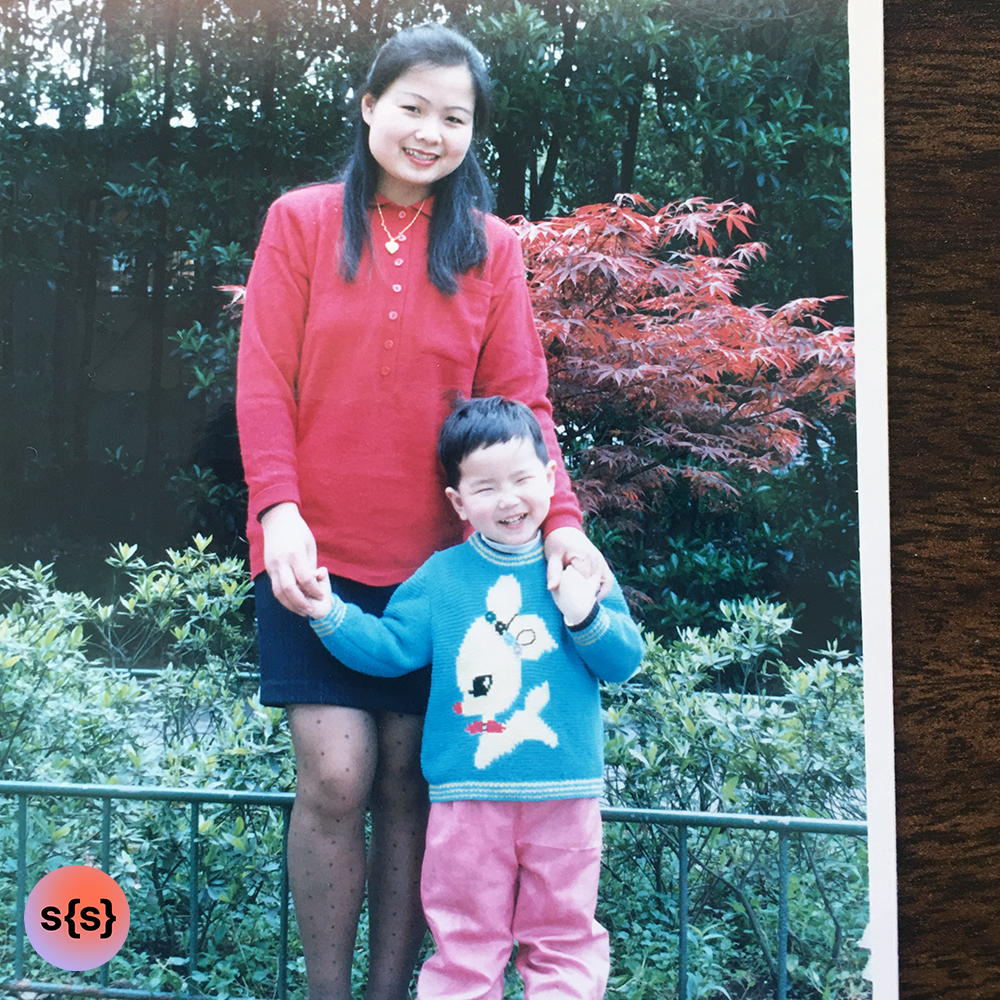

I was born in China when things were still very communist. Everybody got company housing from the state-owned enterprises and for food and goods, we had something akin to a ration card. My parents were both engineers. But when my father passed away when I was 6-years-old, my mom had a choice to make.

- We could stay put. Mom was in her early 40s then – close to retirement age in China at the time. She could’ve stayed in the country where she spoke the language, the country she had lived in for her entire life and live a comfortable life OR

- We could uproot absolutely everything in order to give me a better shot for a future in the United States.

It was no small choice but she was focused on the hope for a better life in the United States When I was 7, my mom and I packed two suitcases and one box. We immigrated from China to Davis, California.

Being an immigrant is not for the risk-averse. My mother gave up everything she had ever known. She bet on her ability to learn a new language and culture and raise a child who could succeed in an environment she had only ever heard stories about. Those aren’t great odds but she knew that if she could pull it off, the rewards could be beyond anything either of us could’ve imagined.

In Silicon Valley, you hear a lot about engineers or product managers who are afraid to take the leap from a FAANG company to an early stage startup because of the risk involved. I get that but I also think the English language needs to have more than one word for “risk.” The risk of shedding your golden handcuffs in the valley is nothing compared to the risk required to uproot your life and moving to a new country where you don’t know the language

To be an immigrant, you necessarily have to take big swings with the odds stacked harshly against you. To be an entrepreneur, you have to do exactly the same.

We’re used to working hard.

I was in third grade when we moved to Davis. My mom’s background as an engineer in China didn’t translate to anything here. She started working in housekeeping at a senior living facility. At night, she took English classes and studied to become a CNA. Once she was a CNA, she decided she wanted the financial security that only a nursing degree could bring. Luckily, my mom qualified for a scholarship, however she would only be eligible if she went to nursing school full time. Reliant on the income of her CNA job, my mom worked four 12-hour shifts a week and spent the other three days a week in nursing school so she could take on the full time course load and earn herself the scholarship.

My mom was willing to work impossibly hard in the short-term to have more security for the long-term – all when she would’ve been retired if we had stayed in Chengdu.

Being an immigrant is never the easy road. Staying put would’ve been easier. Immigrants recognize the value in hard work. So do entrepreneurs.

We’re scrappy.

With my mom at work and in school seven days a week, household responsibilities fell to me. I learned how to cut coupons and manage a budget. I learned what was worth spending money on and what was just as good from the bottom of the bargain barrel. I navigated Davis from the back of my bike and became friends with many peers whose parents were professors I was naturally competitive so these academically-driven kids were the ones I wanted to compete with. I entered the third grade in the United States not knowing any English at all. By the 5th, I was in the same classes as my peers and started on an accelerated course of math and science. I turned those early relationships into a high school internship at a lab at UC Davis. I’m pretty convinced that early internship was a key part of my undergraduate admission into Stanford with a full-ride scholarship.

To be an immigrant, you often have to navigate the world with limited resources. Entrepreneurs have to do the same.

We know that most rules are artificial.

The rules of communist China were wildly different from the rules of suburban America. My mom and I both had to learn new ways of thinking and being in order to better integrate ourselves into our adopted country. For me, it was a lesson: most rules aren’t hard and fast, they’re cultural constructs. If you spend your whole life in one country, you might assume that things are the way they are for good, sound reasons. When you’re an immigrant, you see that many rules and systems are built how they are arbitrarily – or maybe they were built the way they were for a reason that’s no longer relevant. That knowledge empowers you to both navigate the rules and know when there’s an opportunity to blow them up entirely in favor of something more efficient, more profitable or more equitable.

Immigrants know through diverse cultural experiences that there are many ways of looking at the world – or just the hurdle in front of you. Entrepreneurs require that same lens to create category-defying products or spearhead an entirely new category that nobody has dreamed up yet.

We aren’t afraid to acknowledge our own luck.

My origin story is one that ultimately has a happy ending. My mom still lives in Davis, California and enjoys the community that she has built there. She is retired now and spends most of her time tending to her garden. She also enjoys traveling around the world. I received both my B.S. and my M.S. from Stanford University. I’m a product manager at Ketch, a super{set} company, which was co-founded by an immigrant and the son of immigrants. (Go figure.) It’s practically storybook. I’m also acutely aware that not everybody is so lucky. Being allowed to immigrate to the US in the first place was an incredible stroke of luck. We benefited from social programs like free lunches and Medicaid which helped us get by. I was lucky to be surrounded by peers who challenged me and raised the bar. My mother was given a scholarship to nursing school. I was given a scholarship for college.

Pulling off the immigrant life and pulling off the startup life both require risk tolerance, hard-work, scrappiness, and a willingness to bend the rules of what is possible. Success at either also requires the stars to align in your favor. If you lose sight of the hand that luck dealt you, it’s easy to start believing that your successes are yours alone. That’s when you’ve lost the plot. My adopted country likes to boast that it was built by immigrants and sometimes likes to forget that it’s being built by immigrants, still. If we could acknowledge all the ways that immigrants are poised to succeed and contribute, perhaps we could set them up with more opportunities and more luck. Perhaps my story wouldn’t be so storybook.

That might be a long shot, but I’ve bet it all on longer odds before.

Check out open roles at super{set} companies at careers.superset.com

Tech, startups & the big picture

Subscribe for sharp takes on innovation, markets, and the forces shaping our future.

Let's keep in touch

We're heads down building & growing. Learn what's new and our latest updates.